Roger D Metcalf DDS, JD

Forensic Odontology

and Some Other Stuff

Odontologists--remember we need basic, foundational research in all areas of our discipline. Are our procedures scientifically valid and reliable?

Critically examine everything we've been taught. Question the scientific basis of every standard, guideline, best practice, or principle followed.

Keep in mind the quote often attributed to W. Edwards Deming: "Without data you are just another person with an opinion." I would add, if you use incorrect data, you may commit forensic malpractice, and, always remember: "First, do no harm."

We insist on evidence-based treatment in health care, why not in forensics?

Merely saying "we're following the science" without verifying that the "science" being followed is actually true is the same thing religions and cults do.

Doyle v. State of Texas : The Bitemark Case That Started It All

I was very fortunate to be invited to present “Doyle v. State of Texas: The Bitemark Case that Started it All” at the 2019 AAFS meeting in Baltimore at the “Last Word” session. The presentation was intended to be a somewhat lighthearted and noncontroversial look back at Doyle v. State of Texas, 263 S.W.2d. 779 (Tex.Crim.App. 1954) from a historical perspective. My thinking was that we talk about old legal cases all the time, but unless one is really a law geek or involved in this stuff on a daily basis, it might be a bit confusing to keep all the cases straight and what they stand for in forensics. For example, see Frye v. United States (a 1923 murder case from Washington, DC; note: despite what is occasionally reported, this is not a U.S. Supreme Court case). The Frye holding gives us the concept of “general acceptance in the field” as a standard for the admission of novel scientific evidence. The underlying case itself was a more-or-less run-of-the-mill murder case…but the “backstory” is fascinating, encompassing everything from use of an early precursor of the polygraph machine up to development of the cartoon character Wonder Woman.

Now Doyle was certainly not the firstknown bitemark case. We know about a handful of earlier cases such as Ohio v. Robinson in 1870, but Mr. Robinson was acquitted and so there was no verdict to be appealed and reported. But I believe Doyle is the first known reported legal case in the U.S.—“reported” in the legal sense that the case went up on appeal and the holding was reported in a legal journal. And, when I say “the bitemark case that started it all” I mean that this is the case that started us on the slippery slope of admitting bitemark evidence at trial sans rigorous examination of the underpinnings.

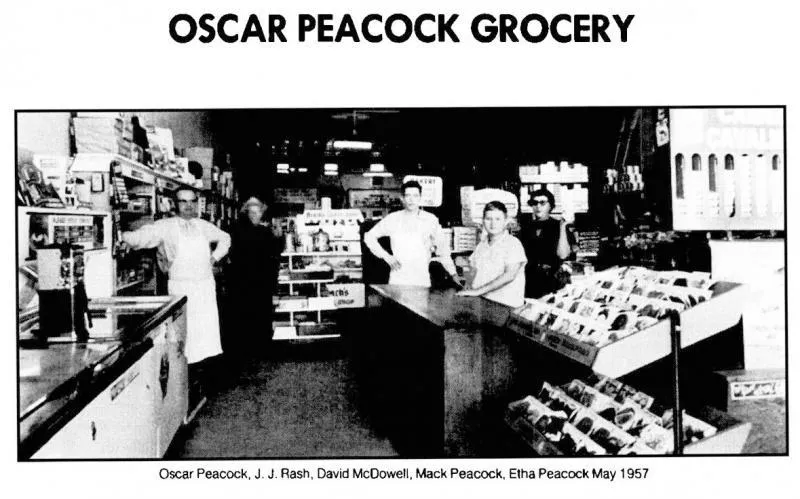

Jimmy Doyle was convicted in 1954 in Stonewall County, Texas, of burglarizing Oscar Peacock’s grocery store in the small town of Aspermont. Sometime during the burglary, he took a bite out of a block of cheese and left the remaining hunk of cheese on the meat counter in the store. Later at the jail, the Sheriff and a Texas DPS Trooper asked Mr. Doyle, who had been arrested in the wee hours of the morning for public intoxication, if he would bite into a similar, but pristine, block of cheese and he did so voluntarily—this was an exemplar bite. The cheese from the grocery store crime scene and the exemplar cheese were sent to a Texas DPS firearms & toolmark examiner for comparison. He made plaster casts of the bites, analyzed those, and then sent the casts on to Dr. William Kemp of Haskell, Texas, a long-time and well-respected member of the Texas State Board of Dental Examiners, for second opinion. Both Dr. Kemp and the toolmark examiner reached the opinion that Mr. Doyle made the bites in both blocks of cheese.

This is NOT the cheese from Doyle!

Doyle was convicted of burglary, and the conviction was upheld by the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals. Admission of the bitemark evidence was not objected to at trial, so that was not preserved as an issue for appeal. The only issue raised on appeal was the claim that when Mr. Doyle was asked to bite into the second piece of cheese, he was essentially making a confession and he did not receive the required warning regarding self-incrimination (Texas had this requirement years before

Miranda). The Court of Criminal Appeals was not persuaded, and his conviction was affirmed.

In Doyle the Court also wrote regarding admission of evidence: “In fact, we fail to perceive any material distinction between the case at bar and the footprint and fingerprint cases so long recognized by this Court.” These features are considered to be “fixed characteristics” of the subject. So in Texas we are not actually required to obtain a court order or ask law-enforcement officers to get a search warrant in order to take impressions of a suspect’s teeth—as long as the subject consents and is cooperative. It’s not a bad idea to do so, though.

Our next known reported bitemark case in Texas came up 20 years later in Patterson v State, 509 S.W.2d 857 (1974). This bitemark case was potentially distinguishable

from Doyle because the bitemark in Doyle was in cheese and the bitemark in

Patterson was on human skin. While that issue was not raised, however, admissibility of the bitemark evidence was

challenged “…because the test results were not sufficiently scientifically proved for reliability.” The uniform Texas Rules of Evidence were not adopted until 1997, but under common law principles evidence still must always meet the criteria of being relevant and reliable. So while I believe there could have been a successful challenge if Patterson had been distinguished from Doyle, unfortunately counsel did not do so and the Court simply stated “We held similar evidence admissible in

Doyle (citation omitted). The objection goes to the weight rather than to the admissibility.”

And then later in Spence v. State, 795 S.W.2d 743, (Tex.Crim.App. 1990), defendant similarly challenged bitemark evidence as not being scientifically proven, and also challenged the constitutionality of being compelled to give impressions of his teeth. The Court once again noted “[t]his Court in

Doyle… Patterson… and Marquez, without discussing what predicate must be laid before bite mark evidence becomes admissible evidence, approved the admissibility of bite mark evidence.”

Such is the power of precedent. Now I am a court institutionalist and believe fully in stare decisis and in sticking to precedents and all that sort of thing. But we see that Doyle and Patterson

started us down the slippery slope of sister courts admitting a species of “scientific, technical, or other specialized knowledge” (words borrowed from the Rules of Evidence) without a critical examination of the foundation of that knowledge simply because Texas' courts had already allowed it.

But, for reasons I will explain, I do not necessarily agree that a “moratorium” should be declared for all bitemark evidence, either. People think they know me, but I like to point out that when I was in law school at Texas Wesleyan (it’s now the Texas A&M School of Law), I did all my pro bono hours for our local Innocence Project. My class was the original law school class to work with the Dallas County D.A.’s office when the then-recently-elected Mr. Craig Watkins was establishing the Conviction Integrity Unit. When I ran (unsuccessfully) for Justice of the Peace, I ran as a Democrat. What I’m saying is, I’m not a hard-core right-wing prosecution hack, despite what some folks may think.

The Dallas County District Attorney's Office has absolutely no connection to this presentation whatsoever!

So, even though I may think there may be issues with positively connecting a suspect’s teeth to a bitemark, please remember even the vaunted N.A.S. Report from 2009 grudgingly advised “[d]espite the inherent weaknesses involved in bite mark comparison, it is reasonable to assume that the process can sometimes reliably

exclude suspects” (emphasis added).

Does the defense bar really want to lose this powerful tool that can exclude an innocent suspect?

Excluding someone may not seem like a big deal, but if you are the person being excluded, it is crucial. And further, if a defendant has exculpatory evidence that he/she is not allowed to present at trial due to a rule made by an agency, could a constitutional issue be raised on the basis of due process/fundamental fairness?

At the 2019 AAFS meeting in the Odontology Section Scientific Sessions on Thursday and Friday, I occasionally heard different presenters talk about the “lack of scientific basis” for bitemark analysis in connection with requirements under Rule 702. I assume they were referring to Federal Rule of Evidence 702, though they did not say for sure. (And, please note, when the Texas Rules of Evidence were adopted, they were virtually word-for-word identical to the Federal Rules, though they have morphed a bit in some places over the years—and this is the case in several other states, as well.)

But I would humbly remind folks that under whichever set of Rules of Evidence they are referring to, Rule 702 is about qualifying the expert witness, not about admissibility of

evidence.

But I would humbly remind folks that under whichever set of Rules of Evidence they are referring to, Rule 702 is about qualifying the expert witness, not about admissibility of

evidence.

The rules regarding evidence itself are in the 400’s section of the Rules—these Rules in the 700’s series deal with expert witnesses. In any case, under whatever set of rules, again, evidence still must be

relevant and reliable to be admissible. In our discussion here, reliability is the crux of the matter.

The rules regarding evidence itself are in the 400’s section of the Rules—these Rules in the 700’s series deal with expert witnesses. In any case, under whatever set of rules, again, evidence still must be

relevant and reliable to be admissible. In our discussion here, reliability is the crux of the matter.

Interestingly, we just had an opinion from our Court of Criminal Appeals in Rhomer v. State, where the majority wrote regarding qualifications of expert witnesses: “[b]ut even if they were not scientific methods [that he used], that would not mean that Doyle was unqualified; an expert does not need to use scientific methods to be qualified. An expert is qualified by specialized knowledge, training, or experience. There is no requirement that the expert’s specialized knowledge, training or experience be based on scientific principles.” Rhomer v. State of Texas, PD-0448-17, 30 Jan 2019. Rhomer is about a motor vehicle accident and the qualifications of the accident-scene-reconstruction expert witness (and there is the unfortunate coincidence for us here that the expert’s surname was Doyle—not related to our bitemark fellow Jimmy Doyle, as far as I know).

The Texas Rule of Evidence 702 reads “[a] witness who is qualified as an expert by knowledge, skill, experience, training, or education may testify in the form of an opinion or otherwise if the expert’s scientific, technical, or other specialized knowledge will help the trier of fact to understand the evidence or to determine a fact in issue.”

In her concurring opinion in Rhomer, Judge Barbara Hervey of the C.C.A. touched on a related potential issue that has bothered me for some time: “TEX. R. EVID. 702. This rule of evidence has been a stalwart and guiding light for the admittance of expert testimony in a criminal action. However, by virtue of its rule-making authority authorized by statute, the TFSC might be able to abrogate Rule 702" (emphasis added).

It will be interesting to see how this plays out in the future.

Roger D Metcalf DDS, JD

PO Box 137442

Fort Worth, TX 76136-1442

ph: +1-817-371-3312

fax:+1-817-378-4882

© 2013 - 2024. Roger D Metcalf. All worldwide rights reserved.

No reproduction without permission.

Neither the Tarrant County Medical Examiner's District, Tarrant County, the American Board of Forensic Odontolgy, the American Society of Forensic Odontology, the Royal College of Physicians, Oklahoma State University, nor any other organizaion mentioned here necessarily supports or endorses any information on this website. Any opinions, errors, or omissions are my responsibility, and mine alone. This site DOES NOT REPRESENT the official views of any of these--or any other-- organizations. Similarly, those other organizations may not fully represent my views, either.